“No man is an island, entire of itself.” So observed John Donne, memorably, in 1624, a year before bubonic plague beset London, killing some forty thousand people. No man is an island—unless isolated, a cognate word whose currency manifests in the term self-isolation, the act of removing oneself from public life until, in this instance, the current plague, a virulent strain of coronavirus, has lifted.

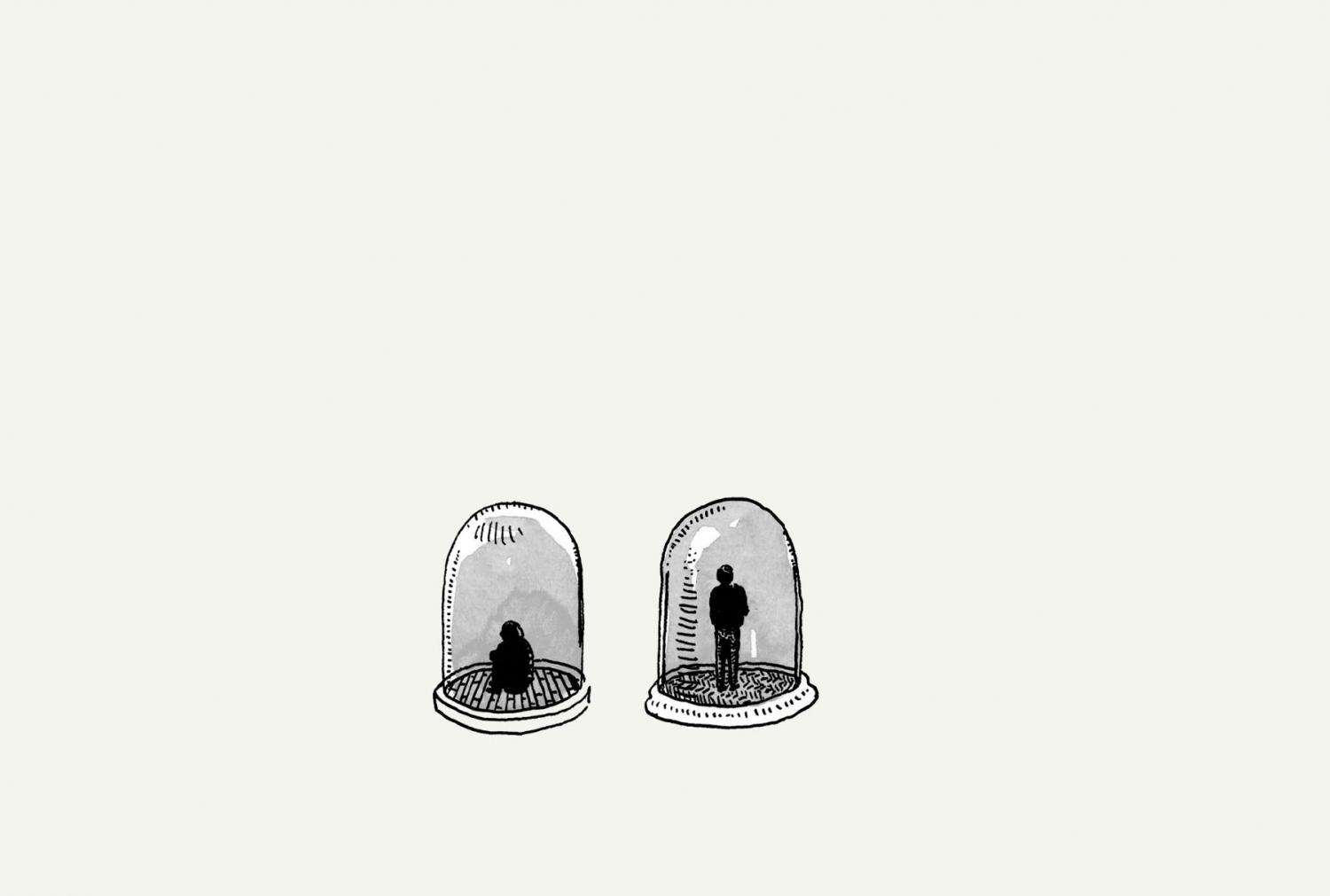

For social creatures like humans, being alone can be psychologically devastating. That fact accounts for the widespread use of solitary confinement as a form of punishment, a practice used to isolate “problem” prisoners, many of whom suffer from mental illness exacerbated by being denied contact with other humans. It is also something that most of us have been getting used to in a prophylactic setting, avoiding offices, classrooms, gyms, restaurants, bars, and other places where infectious disease is likely to lurk.

Even in public we have been asked to be islands, following norms established under the wan term social distancing. It seems antisocial, after all, to require people to keep a distance of six to ten feet in settings such as grocery-store lines, but there’s good reason for it in minimizing exposure to aerosolized pathogens—nasty little critters that travel through a cough or a sneeze. Get sneezed or coughed on by a stranger, and you’d do well to self-quarantine, another newish expression that, in strictest etymological terms, means to put yourself away for forty days—twenty-five days longer than United Nations rules permit prisons to hold inmates in solitary confinement.

This isolation, this distancing, comes at a time when loneliness is already reckoned to be at levels of an epidemic, and being alone is making it worse—almost half of Americans who are “sheltering in place” report a decline in their general mental health. To be alone as a matter of circumstance and not choice can be as detrimental to the health as smoking, obesity, or drug use, in part because it increases anxiety and the body’s production of stress hormones. Great Britain, whose government in 2018 created the post of Minister for Loneliness, had no sooner begun to combat isolation by funding such things as dog-walking clubs and community gardens than did coronavirus arrive, sending all those lonely people back to their solitary lives and solitary worries.

Loneliness is a term never used in a positive sense. The number of the lonely is growing as extended families disappear and, at least in the United States, more and more people live by themselves. (Only about half of American adults, for instance, are married, down from about three-quarters in 1960.) When we speak of isolation, similarly, we don’t mean it to be a good thing. Of course, one can feel alone and lonely in a room full of people, and there are plenty of people in the world who can be alone and content—a state which we describe with the more value-neutral word solitude. It was the distinction between loneliness and solitude that Blaise Pascal was likely thinking of when he remarked, “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” In our time, those who are isolated, quarantined, lonely, and solitary alike have altogether too many opportunities to test that thesis.